- Robert De Niro Heat Movie

- Heat Al Pacino full movie, online

- Heat Al Pacino Full Movie Youtube

- Heat 1995 Film

- The Heat Al Pacino Full Movie

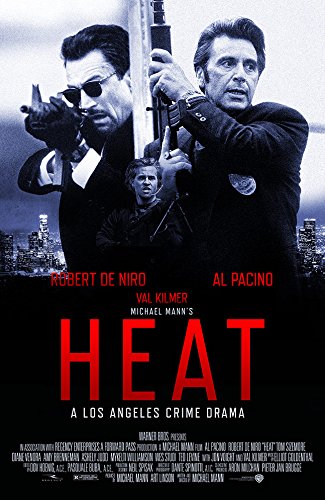

Though it's a tad too schematic, Heat, written and directed by Michael Mann, provides a venue for white-hot acting by De Niro and Pacino. Full Review Page 1 of 5. Watch the full movie, online. 4.5 / 5 stars 94% 86%. 1995 172 min R Drama, Mystery/Crime Feature Film. Robert De Niro Neil. The Heat diner scene is one of the best in the movie, and a panel after a recent screening revealed Al Pacino and Robert De Niro never even rehearsed it.

Posted on Friday, September 9th, 2016 by Ethan Anderton

Heat is a 1995 American crime film written and directed by Michael Mann. It stars Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, and Val Kilmer. De Niro plays Neil McCauley, a p. HEAT Movie Clip - Diner Scene FULL HD Al Pacino, Robert De Niro Thriller (1995) SUBSCRIBE for more Movie Clips HERE: Clip Description.

One of the most iconic scenes in Heat is where Robert De Niro and Al Pacino calmly sit down for a man-to-man chat in an effort to understand each other a little better, both affirming that neither is going to stop what they’re doing, and they’re not going to let each other get in their way. Bringing these two together for a confrontation for the first time was a big deal, and there were even rumors that Pacino and De Niro never shot the scene together, opting to do each part independently of each other.

During a panel we attended after an Academy screening of a 4K remaster of Heat (which should be coming to Blu-ray sometime later this year or early next year), moderator Christopher Nolan confirmed that evidence of the actors working together in the same place at the same time lies in a picture that you can see at the real location the scene was shot in, Kate Matalini’s diner in Beverly Hills. However, it was revealed that Pacino and De Niro never rehearsed the scene before shooting it. Find out more about how the Heat diner scene was put together after the jump.

Al Pacino said the idea not to rehearse the scene came from De Niro. To him, it seemed bit pointless since there wasn’t much movement that needed to be planned ahead of time, and everyone wanted the scene to happen as organically as possible. Director Michael Mann went on to explain even more:

“We decided that we just wanted to talk it through and just save it for the event of shooting it. That’s the only thing we probably did that with. But I tend to not want to rehearse things to the point where I wish I had shot it. That’s a disaster. I always want to stop well short, because I think things work perfect once, and they’ll never be 100% twice. And you want that happening in front of the camera.”

As far as how it was shot, Mann went into more detail, even revealing that most of the footage came from one specific take:

“We talked about the scene, we analyzed the scene and we kind of read it off the page a bit, but we didn’t want to do the scene until we were at Kate Mantilini’s. It was so ingrained that I knew if we lost all the tiny, little organic details, it would be different from take to take. So what I wanted to do was shoot with two cameras, two over the shoulders. And then I also had a third camera shooting profiles that we never cut into the film. So I knew there’d be an organic unity to one take, and then there’d be a slightly different organic unity to another. If you look at it very carefully, if Bob [De Niro] shifts his hand like this a little bit, right in the middle of the dialogue, Al is doing something to counter it, because maybe he’s shifting his position to get closer to a weapon. So most of the scene is all Take 11.”

Wrapping up the discussion about the iconic diner scene, Christopher Nolan asked Pacino and De Niro after the late night of shooting that scene, which didn’t begin until about 1 am, if they knew they “had it.” Of course, both of the actors modestly said they had no idea, and they never knew that. But Michael Mann confidently said, “I knew we had it.”

Check out our other story from the Heat panel where Al Pacino confirmed an interesting detail about his character. And if you want to watch the full segment where they discuss the diner scene, here’s video from the event:

You can watch a little over 30 minutes of the panel from this event at the Oscars YouTube page right here.

Cool Posts From Around the Web:Robert De Niro Heat Movie

Related Posts

Welcome to That One Scene, a semi-regular series in which Task & Purpose staffers wax nostalgic about that one scene from a beloved movie.

It was the winter of 1995 when director Michael Mann unleashed the heist flick Heat on an unsuspecting world. From start to finish the 170-minute-long caper is overloaded with star power. Film legends Robert De Niro and Al Pacino engage in a game of cat and mouse, as Pacino’s hot-tempered Lt. Vincent Hanna and De Niro’s cool and professional bank robber, Neil McCauley, spar relentlessly.

Heat Al Pacino full movie, online

And even though the iconic, and entirely unrehearsed “restaurant scene” is basically just several minutes of unadulterated acting prowess, that's not what we’re here to discuss. No, we’re talking about a different moment. Yeah, you know which.

Heat Al Pacino Full Movie Youtube

For this edition of That One Scene, we’ll be discussing the iconic bank robbery and shootout on the streets of Los Angeles, and that makes us very excited, since the firefight in Heat is the greatest example of fire and movement ever depicted on screen.

When McCauley and his crew of ace stick-up men, Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer), Michael Cheritto (Tom Sizemore), and last-minute replacement Donald Breedan (Dennis Haysbert), go through with their plan of a daylight bank robbery in downtown L.A., it quickly devolves into chaos and bloodshed after they exit the building with their bags of cash and find a police ambush waiting for them.

What follows is a shootout that was so good, in fact, that the clip was often played for fresh out of a boot camp Marine privates at the Corps’ School of Infantry, to show them an example how the concept of bounding overwatch was applied in practice.

It’s easy to see why: In the span of roughly 10 minutes, the film’s characters provide each other with cover fire and effectively suppress their foe (in this case, the cops), communicate effectively, and move just like trained infantrymen. Could Neil or Chris be a former grunt? Perhaps.

In favor of that argument is the military-like movements of the characters, which appear early. The crew casually walks into the bank, their M-4-like and Galil rifles well-hidden, suggesting a high level of training and discipline. All three quickly dispatch the security guards, then order the crowd of customers to the floor. Though it sounds like a standard bank robbery scene, they move and operate as a well-trained force, with Neil MacCauley keeping his finger straight and off the trigger and Chris passing bank keys to his partner using his non-shooting hand. Little is said. Much like a Marine team leader, rifleman, and automatic rifleman, they all know their individual roles.

Moving outside, the scene briefly cuts to Lt. Vincent Hanna being warned of a robbery in progress before the crew begins coming out of the bank. Everyone gets in the car except a smiling Chris, who sees two cops in front of him. He fires a heavy burst towards the officers, and unlike most other action movies, the bullets are accurately fired from the shoulder instead of the hip. This ain’t Rambo, ladies and gentlemen.

The robbers eventually get in the car and begin driving away, but their vehicle is disabled in a hail of police gunfire. In front and behind them are road blocks manned by dozens of officers. But that, as we see, is not a problem.

Chris and Michael are the first to exit the car, and they immediately move behind the cover of cars in the road. While maintaining good dispersion, they lay down a blistering hail of suppressive fire on the officers and force them to take cover. “Go!” Chris yells to Neil, who then runs closer to the roadblock and finds his own cover.

What is happening here is literally a textbook Marine rifleman tactic: “fire and movement consists of individuals or fire teams providing covering fire while other individuals or fire teams advance toward the enemy or assault the enemy position.”

They continue the leapfrog maneuver with great success. Though they briefly communicate (“Go!”), Chris and Michael mainly follow their team leader (Neil), who acts as a fighter-leader for the unit. And as they get closer to the police blockade, the bank robbers’ bullets are more accurate and lethal. They have walked into an ambush and are successfully fighting their way out.

At one point, the camera zooms in on the actions of Chris for about 15 seconds. And the brief aside is worth breaking down further. Upon hearing the “go” command of Neil, Chris bounds forward towards the cover of a car and immediately begins firing so his teammates can move. He fires to the front so that Neil can move, then fires to the rear so that Michael can move. Then, he runs out of ammo. Does he freak out?

Not at all. Chris immediately drops to a knee while simultaneously removing the spent magazine. He tucks the rifle under his arm, grabs another from his vest, inserts it, and smacks the rifle with the meaty portion of his hand. He knows to do it that way because he’s aware combat stress negatively impacts fine motor skills. And the reload is fast — in line with your average Marine grunt.

Still, the bad guys can’t end up winning this one, and not just because Al Pacino is better than Robert De Niro (yeah, we said it). They are, after all, bank robbers and this movie needs a happy ending. And besides, the cops are able to lay down effective fire of their own: a pair of officers appear to wound Michael with glass and possible bullet fragments, and an equally well-trained detective, firing with both eyes open, spots Chris to his side before shooting him in the neck.

And then there’s Hanna, who pulls off a sniper-like shot with an FN FNC-80 rifle. As Michael fires blindly at officers behind him, the camera zooms in on Hanna, who moves the rifle’s buttstock high on his shoulder to get the proper cheek weld. He closes his non-shooting eye to focus on the target and takes a breath. He releases. Michael turns with a little girl in his hand. Hanna fires and hits him directly in the head. The girl is saved and the robber is dead.

One thing that’s unmistakably missing from this sequence — compared to the host of cinematic shootouts that preceded it — is the random spray and pray hipfire. Every single shooter, from the cops to the robbers, fires with their weapon pressed firmly in the shoulder, while aiming down their sights, and doing their best to use cover.

And then, there’s the fact that the shooters actually reload their weapons, rather than indiscriminately firing hundreds of rounds from a magazine that only holds 30 — yet another departure from previous movie gunfights.

Heat 1995 Film

“It's the first time you've ever seen an actor do a reload all the way from beginning to end, with Val Kilmer with the AR,” said Taran Butler, a professional three-gun shooter who's spent years working behind the scenes on a range of action films as a firearms instructor, to include the second and third installments in the John Wick franchise.

There are other elements beyond the technical that help the scene stand out — mainly that it felt like it was directed and choreographed by people who’d actually spent time shooting, whether it was on the range, or downrange, to include Mick Gould, a British SAS veteran, and the film’s technical weapons trainer. Then there was Mann himself.

The Heat Al Pacino Full Movie

“What I love about it, is that Michael Mann knew guns,” Butler told Task & Purpose. “That shootout, what's so great about it is he turned up the volume. He recorded actual live fire on set, to get that echo through the streets, and that's why the action sounds so ominous and scary. You know, when you're around gunfire without muffs on, or you're ever downrange, you get that chilling feeling.”

The end result is a shootout that accounts for just a fraction of Heat’s total runtime but remains the single most memorable and influential sequence of the entire film.

RELATED: The lingering appeal of Col Jessup’s courtroom tirade in ‘A Few Good Men’